How the First Step Act Created the Illusion of Change Without Real Progress

The First Step Act (FSA) was passed in 2018.

It was sold as a massive, once-in-a-generation step towards criminal justice reform. At the heart of the FSA was Section 404, a provision designed to rectify the inherent injustice in the practice of punishing crack cocaine offenses 100 times more harshly than powdered cocaine offenses, despite the two substances being pharmacologically identical. More specifically, Section 404 is touted as a long-awaited antidote to an irrational injustice that has unfairly destroyed the lives of countless African Americans.

Because of the FSA, people now mistakenly believe that this injustice has been put to bed once and for all. This is highly misleading. Sadly, not even the most blatantly unfair aspect of the criminal justice system was remedied by the First Step Act.

To say that federal law treats crack cocaine offenses more harshly than powdered cocaine offenses is a gross understatement, as it fails to adequately capture the inherent unfairness and strikingly unjust disparities undergirding the American justice system. For decades (since the mid-80s) federal law has treated crack cocaine offenses more harshly than powered cocaine offenses—100 times harsher, in fact. Practically speaking, this radical disparity—100 to 1!—means that an African American who is convicted for a handful of crack—a substance that is less expensive than powered cocaine—might wind up serving many decades or even life in prison (with no parole), whereas a white person convicted of selling pounds of powdered cocaine might receive a slap on the wrist.

In case you think I’m downplaying the harm of crack cocaine—I’m not.

It’s a horrible poison that wrecks lives. To reiterate my earlier point: it is a well-established scientific fact that the two substances (powdered cocaine and crack cocaine) are pharmacologically identical. Therefore, while both forms of the substance have damaged innumerable lives, my focus here is on the decision to punish crack cocaine 100 times more harshly than its powdered counterpart (cocaine), especially when 90 percent of the defendants convicted of crack cocaine offenses are African American. That is my point.

At any rate, here’s a little context. Contemporaneous with the advent and subsequent proliferation of crack cocaine in America in the mid-80s, the 100:1 penalty scheme for crack cocaine offenses (versus powdered cocaine offenses) was created, a penalty scheme born out of the hysteria surrounding the drug and consistent with the rhetoric of “the war on drugs.” The problem is and always has been that the new law was not based on scientific or empirical evidence. In other words, the glaring disparity in sentencing did not exist because of the different degrees of harm caused by each substance, as there is no difference in the chemical makeup of the two drugs. The only difference between them lies in who uses and sells the two substances.

To that end, as Harvard Law School graduate and civil rights hero Alec Karakatsanis aptly pointed out in his book Usual Cruelty, “[f]or the first seven years that the disparity existed, not a single white person was prosecuted for a crack cocaine offense in seven of the largest American cities.”

And when the smoke settled after decades of federal courts tossing young Black men in prison for a lifetime because of a small amount of crack, it quickly became apparent that a whopping 90 percent of defendants convicted of a crack cocaine offense were African American—90 percent. With that in mind, it becomes blatantly obvious that the federal government was not fighting a war on drugs; rather, it was fighting a war on drugs used by African Americans.

So we have a substance (crack cocaine) that is overwhelmingly used by African Americans in economically disadvantaged parts of the city, a substance which, from a scientific standpoint, is identical to another substance (powdered cocaine) overwhelmingly used by a different culture and socioeconomic class; but the substance used predominantly by African Americans is punished 100 times more harshly. On top of that, consider what drives the demand for crack cocaine in those impoverished areas—relative to powdered cocaine, it is dirt cheap, not to mention that it can be bought in $5 units. In other words, crack is prevalent in poor neighborhoods for the same reasons that 40 ounces of malt liquor are common—it’s cheap and can be purchased in small units.

Imagine if alcohol were illegal today (as it was in the 1920s). And suppose that selling malt liquor was treated 100 times more harshly under the law than selling, say, Johnnie Walker Blue Label scotch, alcohol that is used predominantly by older white men. Admittedly, I have no concrete data to support this, but it’s safe to say that you don’t see many people in wealthy enclaves (such as Highland Park, in Dallas) and even in middle-class suburbs drinking malt liquor; conversely, you don’t see many people in the housing projects drinking $300 bottles of scotch.

Such a law would, without a doubt, be expressly designed to unfairly target a particular socioeconomic class and culture. This is nothing new. Historically, the criminalization of the use and sale of certain substances was designed to target particular groups at specific historical moments. (Jamie Fellner. (2009). Race, Drugs, and Law Enforcement in the U.S., 20 Stanford Law & Pol’y Rev. pp. 257, 263 in Usual Cruelty)

Returning to the disparity in crack cocaine and powdered cocaine sentencing, fortunately, all was not lost. Given that the law had no legal or scientific basis—coupled with the fact that it had a disparate effect on African American defendants—people eventually began to demand change, even the ultra-conservative U.S. Sentencing Commission. Finally, after more than two decades of enforcing this senseless law, Congress passed the “Fair Sentencing Act.” Inexplicably, it only reduced the disparity to 18:1. Still, it was a massive change. And thousands of African American defendants serving unconstitutional sentences under a law that had no legal or scientific basis were suddenly eligible for immediate release. But the celebration was short-lived. As it turned out, the “Fair Sentencing Act,” wasn’t so fair.

Problematically, the Supreme Court held that the new penalty structure was not retroactive, meaning that it would only apply to any defendant sentenced after August 2010. Put differently, even though the law was held to be unconstitutional and determined to have no legitimate basis, the thousands of prisoners sentenced under the 100:1 disparity (from the mid-80s until 2010) were ruled ineligible.

This glaring injustice persisted for another decade. And then, when it looked like all hope was, in fact, lost, the First Step Act came to the rescue—or at least that’s how it was pitched. Far and away the most widely touted feature of the Act was Section 404 (the centerpiece of the First Step Act), which was designed to eliminate the unfairness of the 100:1 sentencing ratio regarding crack cocaine versus powdered cocaine, making the reduced 18:1 penalty structure retroactive. Yet again, the thousands of African American men and women who had been unfairly denied eligibility in 2010 under the so-called “Fair Sentencing Act” had hope.

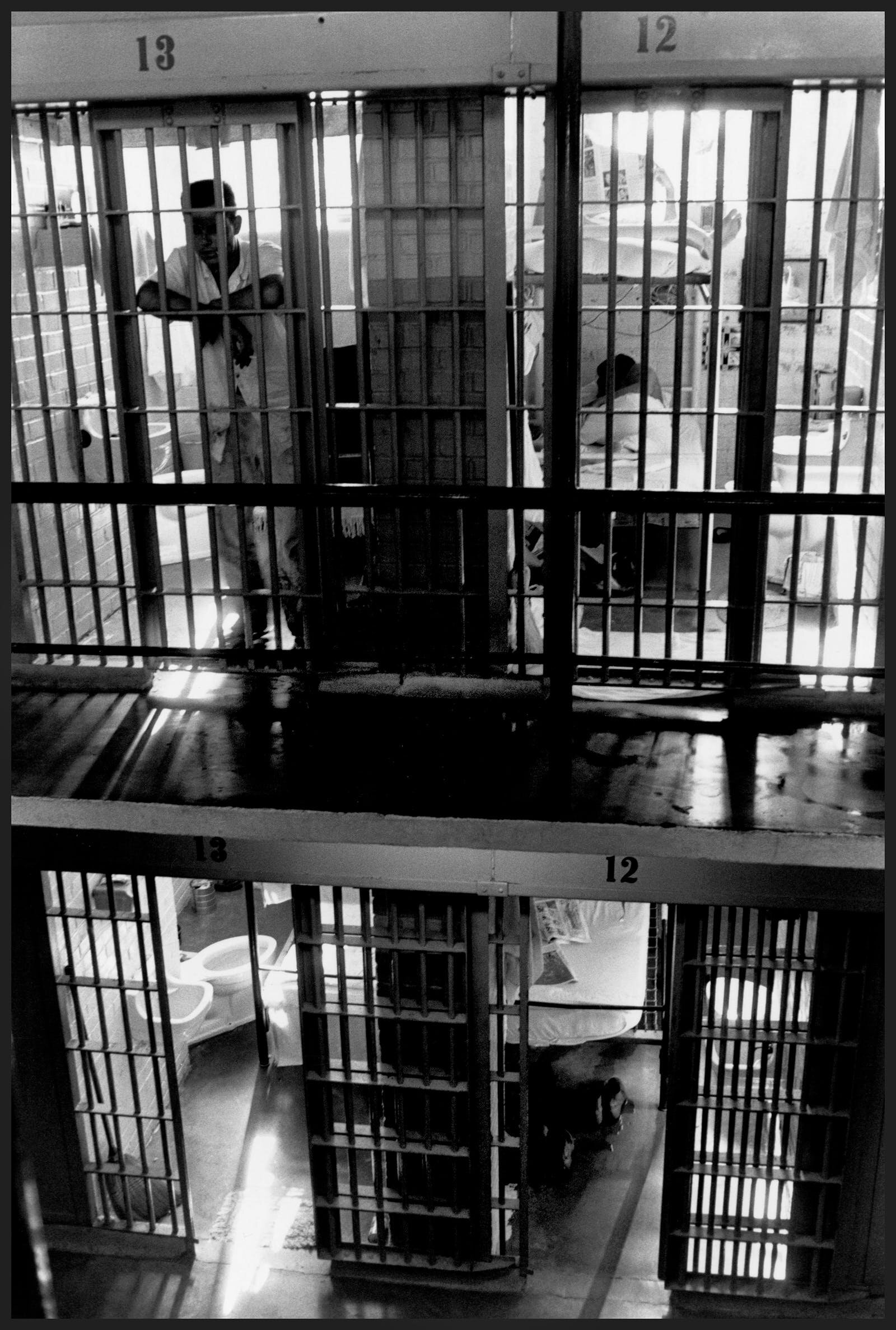

For these thousands of men and women who had languished in prison for decades under an unfair law that had been found unconstitutional (but was not retroactively rectified), the reduction had immense practical value, as it wiped out the remainder of their prison terms and meant immediate release. Prisoners, of course, are acutely attuned to changes in the law such as the First Step Act. And when these incarcerated individuals heard about it for the first time, they were filled with joy and hope. There was a lot more smiling throughout prisons, and you could see a wave of relief wash over them. New life was breathed into them. Their spirits were lifted. Although it was likely to take a couple of months for them to use the new law to get a release from the courts, we promised to keep in touch.

That was more than two years ago, and they are still there. In fact, they are not going anywhere. To be sure, I have not been a first-hand witness to a single person who was eligible for release under Section 404 actually getting their motion granted. They were all denied, one after another. The hope that the First Step Act promised proved false; the victory it represented proved pyrrhic. And their joy vanished just as quickly as it appeared. In the end, it was a gut-punch to the very men and women it promised to free, to the very men and women that it was designed for. It is hard to convey the depth of emotion that this false hope elicited, but I watched as the air was let out of their inflated personalities, a slow diminishment of their hopes and dreams.

I’m sure this doesn’t jibe with your understanding. After all, didn’t Ivanka Trump just talk about this act in her speech at the Republican National Convention, when she mentioned the new law signed by her father that undid decades of injustice to the African American community? She did. She was talking about Section 404 of the FSA.

So how is it possible that all of these men and women are still in prison under a law that everyone agrees is unconstitutional and racist on its face?

Like so many things in the American justice system, there’s a trap door.

It works like this: the FSA is passed. A prisoner was given 30 years in federal prison (with no parole) for an amount of crack that would fit in one’s palm. Between the reduction of the disparity and the FSA’s retroactive ruling, a crack cocaine prisoner’s new Sentencing Guideline is, say, 10 years. The prisoner has already been in prison for 20 years, which should mean immediate release. But not so fast. Yes, the law has been changed; yes, the FSA made it retroactive; but a judge has discretion over whether to release the prisoner, reduce his sentence, or keep him caged. And believe me when I tell you that they exercise that discretion.

In fact, the judges have near-untrammeled discretion to deny said inmates any relief. If the prosecutors argue that reducing a prisoner’s sentence or releasing the prisoner would put the public in danger, then that is that. Good luck winning such an appeal.

To be sure, the FSA is the antidote for the crack cocaine sentencing injustice on paper. In practice, however, it is a hollow reform. It’s a prop that is used to sell change and equality under the law.

I live within 50 yards of three African American men who were sentenced under the 100:1 ratio. Between the three of them, they were convicted for a handful of crack, and their cumulative sentences equal more than 100 years in prison with no parole. First, there is Marcus.

He was given 30 years in prison with no parole for a small amount of crack (there was no violence in the case). He has served 22 years so far. This is his first time in prison. He was arrested at 22 years old; he’s now well into his 40s. Marcus has six children and grandchildren, one of his sons plays college football, and all of his children are productive members of society who support him emotionally. Marcus is upbeat. He’s not a menace in prison, nor is his behavior problematic. It’s quite the opposite, in fact. He has a knack for designing innovative fitness classes that he runs. He motivates people who are struggling with their weight. And he’s adept at using nutrition science and fitness to change their lives. His classes are always booked. Even though he’s been in prison for more than two decades, and even though he is eligible for immediate release, he is still there because of the aforementioned judicial discretion. In short, the First Step Act (Section 404, in particular) was passed because of men like Marcus, as he embodies the unfairness of the old crack law—he was a young, nonviolent, low-level African American drug offender who had never been to prison and who was caught with a small amount of crack, but still received 30 years in federal prison.

Yet the government strained to keep Marcus in prison, filing a 40-plus-page motion that used every piece of inflammatory information it could dig up to persuade the judge to keep Marcus incarcerated, including dismissed charges, 25-year-old juvenile charges (Marcus is in his 40s), uncharged crimes, irrelevant petty prison disciplinary reports, and more. Never mind that after the new law came into effect, Marcus’s new Sentencing Guideline range dropped from 30 years to life in prison down to about 12 years in prison (and Marcus has already served 22 years!).

And then there’s C.J. He spends his days working tirelessly on his case. He, too, was sentenced to 30 years in prison under the 100:1 ratio. He was charged with just five grams of crack, but he has been in prison for about 15 years, with 15 to go. And even though he qualified for immediate release under the new law, he was denied relief. Why? While in prison, years ago, he was involved in a fight; therefore, he is a “danger to the public.” This single fight (in a 15-year span) was an anomaly. Still, the court clung to it, using it as a thin justification to deny his immediate release or even a sentence reduction.

The third gentleman was also denied relief because of a petty prison disciplinary report. This nonviolent, low-level drug offender has been in prison for decades. The FSA was a cruel joke to him and his family.

When it comes to the FSA, one must really read the fine print. The vicious federal government prosecutors have no mercy, and will use some 20- or 30-year-old juvenile charge, an old dismissed charge or a prison disciplinary report to label the prisoner as a “danger to the public.” They fight tooth and nail against the overwhelming majority of motions filed by African American prisoners who qualify for immediate release under the FSA.

And they do more than fight—they win. According to the Sentencing Report, of the 13,335 prisoners who filed a motion to reduce their prison sentences, only 2,387 motions were granted as of January 2020.

Immediate release under the FSA is a running joke in prison. Hearing politicians, celebrities, and gleeful family members telling prisoners who are on the front lines about this new miraculous First Step Act is sort of like someone fighting a battle and listening to the media talk about how the fighting has stopped and the battle has been won. It’s an affront. People buy into whatever they are fed when it comes to criminal justice reform.

What’s more, the numbers are misleading. Most of the prisoners who were released under Section 404 of the FSA had already served two or three decades in prison for a handful of crack and only had a couple of years remaining on their prison sentences anyway. The federal government had already taken their pound of flesh, yet the public believes that the floodgates were opened. Hardly.

In short, judges have been denying these motions as quickly as they are filed.

The three prisoners that I mentioned were sentenced in ultraconservative areas—e.g., Waco, Texas, and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. In areas such as these, older white judges are crushing these African American prisoners with denials of their FSA motions (which seek immediate release or a sentence reduction), just like they crushed the same men and women decades earlier for a handful of crack. If you are under the illusion that this new law has rectified the injustice, you are mistaken. I implore you to open your eyes and dig deeper.

When Marcus’s motion for immediate release was pending, he conveyed to me that his court-appointed attorney was conditioning him for a denial. In particular, Marcus said that his court-appointed attorney was anxious and confused, telling Marcus, “I don’t know why, but the judge just denied another one of my [Section 404] First Step Act motions; it’s the fifth one this week.” His attorney’s incredulity about why the judge would keep denying prisoners a release or even a partial sentencing reduction captures the current state of affairs perfectly.

In short, does Section 404 of the First Step Act make retroactive the reduced 100:1 powdered cocaine versus crack cocaine disparity to 18:1? It does. Does it shorten the Sentencing Guideline ranges (which drive and determine a federal defendant’s prison sentence) by decades in most cases, resulting in the person’s eligibility for immediate release? It does. But to actually secure release under the new law? That is another story entirely. Plainly, it’s all discretionary. That keyword—discretionary—is routinely lost on the public and even the legal community.

Sure, the media tells the stories of the relatively few men and women who were released because of this miracle that they call the First Step Act. Such success stories abound. But for every success story, there are many nonviolent offenders who were sentenced under the 100:1 ratio, are serving many decades in federal prison, and are qualified for immediate release, but have been denied because some cruel prosecutor crafted a 40-page legal brief that used every piece of inflammatory information he could find to paint the prisoner as El Chapo. Of course, you will never hear about those stories, because they are inconsistent with the narrative of massive criminal justice reform, which is in high fashion.

In sum, rather than ameliorating the intractable problems that created injustice en masse, the centerpiece of the First Step Act has only served to create the perception of much-needed, long-overdue change, an insidious effect that sated the public’s appetite for change. In other words, the minor tweaks and superficial changes represented by the First Step Act were not designed to reverse the gross injustices that pervade the American system of justice; rather, they are superficial changes masquerading as powerful fundamental changes, a marketing effort designed to quell the steadfast and sustained demand for justice and to maintain the perceived legitimacy and fairness of the American justice system.

Now everyone can rest—the First Step Act has reversed decades of injustice! This is a carefully cultivated illusion peddled by the media and the politicians. But the reality is much darker.